We’re back to continue our look at what the metaverse could mean for L&D, training and simulation. In part one, we asked what is (and isn’t) it and who is building it. In this part we’ll start to look at how it’s structured and some of the challenges that lay ahead, not only in creating the metaverse but for organisations to be able to adopt it into their ecosystems.

Even before the term re-surfaced to become the defacto catch-all word for everything immersive moving forwards in 2021, many companies were already looking at how the future systems could/would/should be interconnected and interactive between real physical spaces and digital layers of data and representation.

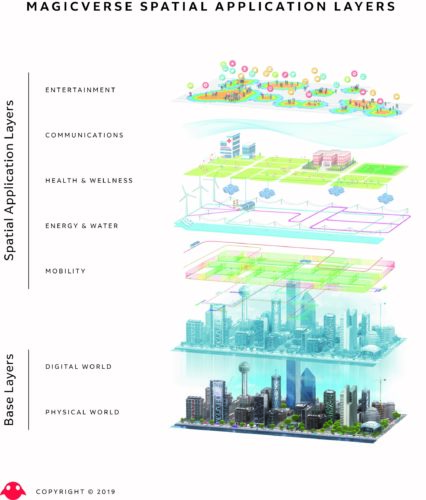

Like with the metaverse today, each company had their own definition or brand to sell in order to capitulate upon the land-grab opportunities being presented. One of the clearest infographics however came from Magic Leap, when they revealed their plans for the Magicverse. At a high level, this emergent system of systems shows the layers we alluded to in part one of this blog post series – the interoperability of data between networks and layers to enable persistence and location-aware experiences for users.

Whilst this doesn’t reflect or tell us anything about how the metaverse will be structured, it’s important to help us understand the complexity of the systems that will eventually form the network of layers necessary to allow data to flow between the portals we’ll visit for work, play and learning in the future.

One of the main discussions occurring currently is whether the metaverse definition remains true to the original intention, being solely VR-based, or whether it can be expanded out to include other facets of XR. If it is the latter, then bringing digital content to merge into the real world, at precise locations based upon a user’s (or their devices) orientation and activity, will be key, based upon a system such as the above.

However this is all very functional and not very exciting, although it does allow for some powerful enhancements for work, learning and play. Things get interesting when we think about structuring experiences as a series of inter-connected worlds, or portals or verses even. The open software layers and hardware interoperability necessary to enable this start to become problematic for enterprise use though.

If this metaverse is to exist to be entered for work purposes, then enterprise IT and security policies are likely to impede connection. Many organisations restrict or block internet access for employees, or filter traffic from devices. If users can be anyone or anything online, then how will this be acceptable to the policy-makers? If the metaverse is to be the next evolution of the internet and accessed via a future form of browser, then these will need to have controls and limitations to keep users “safe” at work.

Technology Gaps : There are already considerable accessibility gaps with the internet, in terms of who has access to it and with what devices. Places of work and education are going to need to heavily invest in immersive technologies in order to be able to enable entry points into the metaverse. If our ability is visible through technology or our virtual representation, will the benefits of online personas work against us to continue widening these gaps of the haves and have-nots.

Ownership : In 2021 the battle for the metaverse (re)commenced, with many organisations laying claim to be building or providing or shaping it. A single entity owning and controlling the metaverse, a centralised decentralised system, is against The 7 Rules. Whilst it’s possible to argue this is also already the case with the internet (albeit with more owners/controllers), will an organisation have to accept this and relinquish control of their own systems in order to be able to access and remain relevant?

Rules and Laws : What happens when the metaverse carries as much weight as a country but operates outside of traditional physical borders? How will the rules, laws and operational guides be defined and by whom? We already see bad faith actors operating across social media but also the potential positive powers too. With great power comes great responsibility but will the crowd police itself or will organisations need applicable filters to apply.

Ecological Impact : One aspect often linked to the metaverse is blockchain / cryptocurrencies (2/3D assets ownership as NFTs) which are mostly terrible for the planet, through electricity used to mine, mint and exchange. As current perceived values make for ever-increasing interest and lust of ownership and involvement, these costs are only increasing too. Companies looking to be carbon-neutral or reduce their impact upon the planet have few options available if they want to be involved or associated with the metaverse.

Distraction Technology : Like many emerging technologies, a valid use case helps organisations understand benefits over hype. We’ve also seen technology hinder humans achieving their goals due to barriers to entry, learning curves and users being overwhelmed by the experience, either through the assault on the senses or getting lost in the game, distracted from their objectives. Theoretically the metaverse could be all these things dialled up to 11 so how will we ensure our company time is spent wisely and effectively.

Representation : You can be anything online, same with the metaverse but will we be expected to make avatars that look like us, or our desired version as we wish to be seen, or will we be turning up to virtual meetings as a lobster, a unicorn, a dragon or any other imaginary virtual being? What will be acceptable will likely fall to organisational policy but we all need to ensure that our biases in the real world aren’t amplified in the virtual.

There are likely many other problems, perceived or actual, which will become apparent over time, or will fluctuate between regions, organisations and generations. Donald Clark has recently listed a series of problems he sees with the metaverse and 20 reasons why it might not work. Whilst not related or designed specifically to be a comment on the metaverse, the Augmented Reality data overload shown in HYPER-REALITY by immersive artist Keiichi Matsuda, highlights potential problems coming our way in the next couple of years.

As we write and post this towards the end of 2021, The Year of the Metaverse (we kid), the noise will only increase throughout 2022. In actuality, very little is likely to happen that will impact L&D, training and simulation next year, other than newer immersive technology devices for AR and VR will continue to improve fidelity and outcomes where use cases have already been validated. Whilst this means greater scale of deployments and the number of organisations embracing XR, the metaverse is still a few years away from being built yet. Just remember this when someone tries to sell you their immersive app or platform; if it goes in but not out again, if it’s not open or interoperable, it’s not the metaverse.

In part three of this series, we take a look at how fictional metaverses might impact a real-life one, and where Web 3.0 does (or doesn’t) come into it all.

We’re always happy to talk to you about how immersive technologies can engage your employees and customers. If you have a learning objective in mind, or simply want to know more about emerging technologies like VR, AR, or AI, send us a message and we’ll get back to you as soon as we can.